Olivia Ikey

Inuit Studies Conference (2022)

"When we say we want culturally relevant it doesn’t mean having igloos. It means we understand the land and how we could manage together with the land and with professional architects and everything."

Most design strategies currently deployed in Nunavik not only come from the South but also do not meet the actual sustainment needs of Northern villages and the Inuit way of life. Building soundly and sustainably in Nunavik ideally means a design outlook and approach that is rooted in and respectful of Nuna. Inuit knowledge of the land draws on the technical and poetic potential of its resources to be wisely used in Northern construction, which is not the case at present.

The effects of climate change and ill-suited designs and construction strategies continue to impact the durability and efficiency of buildings, particularly when systems and components are not adapted to evolving conditions and local upkeep capacities.

Also, acutely aware of Nunavik’s dependence on fossil fuel for heat and power, Inuit are dedicated to seeking out cleaner, more reliable energy sources and technologies.

What We've Learned

Realities

Paths for Change

Efficient and sustainable housing environments do not have to be boring. Dwellings that share walls in multi-family residences help the occupants to reduce energy consumption while optimizing their comfort. Single family houses with climate-appropriate windows can be wisely placed to block harsh winds, be more energy efficient by taking advantage of the sun, and manage views respecting Nuna.

Unused materials found in the community can also inspire repairs to make homes more comfortable and efficient in wintertime. For example, protecting the entrance and porch with a simply built snow deflector could facilitate access to and from the outdoors in the event of a snowstorm, while maintaining views. Sound yet simple, low-tech construction techniques can truly optimize an efficient home.

On a larger scale, the transition toward renewable energy sources and technologies is underway and represents a wealth of opportunities for effective and lasting change in both planning and building.

Calls to Action

61. Prioritize low-tech and passive systems

Implement simple and easily repairable building systems over costly technologies to enable households to have control over their own comfort.

62. Build the perfect walls

Expose interior wall components (structure, pipes, wires) or make them easily accessible to minimize the use of costly or inappropriate materials, such as gypsum boards.

Install isolating materials outside (over the structure).

63. Think of energy-efficient siting strategies

Encourage building configurations or groupings that reduce the impact of winds/cold weather to use less energy for heating (joined housing units sharing partition walls, compact siting of detached buildings, etc.).

Promote proximity between buildings and to services to reduce the need for vehicle fuel.

64. Inform residents about sustainable systems

Provide information to occupants/owners on how to use mechanical systems.

Raise awareness about the impact of certain energy consumption practices (e.g. opening windows to aerate in winter).

65. Further energy transition endeavors

Promote strategies (wind, solar, hydro) that are acceptable to and beneficial for communities.

Optimize sustainable planning opportunities afforded by the transition.

A beneficial and sustainable relationship between land and community rests on the expression of an Inuit “sense of place” that extends to include cultural activities. The camp is one such essential place to support and maintain Inuit identity and well-being.

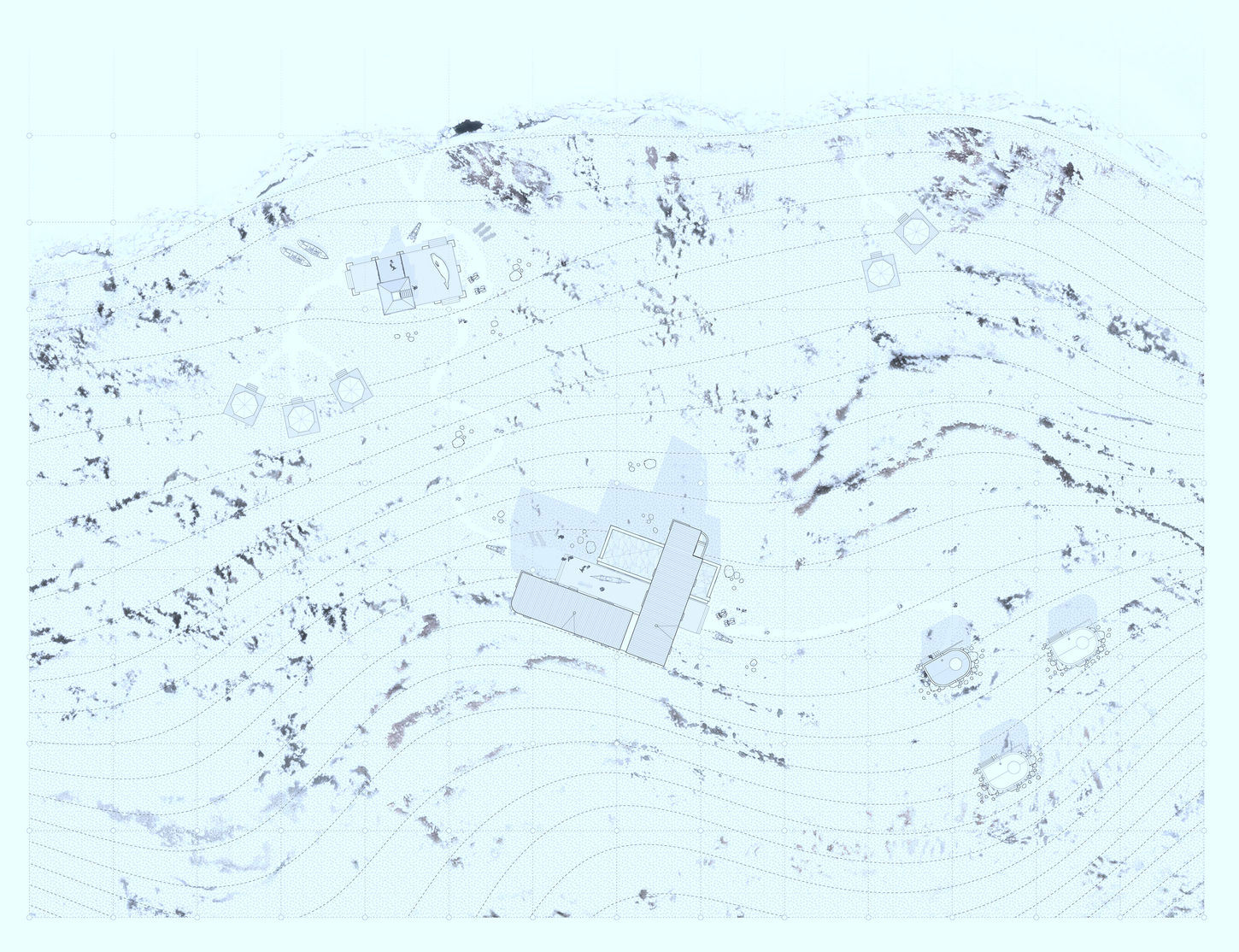

However, despite its proximity, the land is not always accessible to all. This design project facilitates access to the land. It benefits many by creating spaces for the transmission of traditional and contemporary knowledge and providing a restorative space. A main building offers a workshop, as well as oral teaching/interaction rooms. The “low tech” kitchen requires few furnishings, like in a vernacular cabin. Separate cabins allow for introspection and are linked to the land.

Overall, narrow volumes have a limited footprint. The rooms are smaller to reduce the need for heating. The “breathing” envelope is well insulated (sacks of goose feathers) without vapor barriers for air circulation, in accordance with cabin construction; this technique leaves the wood structure exposed inside. Foundations (gabion, piles) are “light footed” to preserve the land. Other construction materials (adobe, rammed earth, charred wood cladding) and assembly techniques are locally sourced.

By P.-O Demeule, École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, 2019

Resilient Architecture Based on Inuit Qaujimajatuqagangit (IQ)

Innovations: Thinking Outside the Box

References

Open Access

Herbane, H (2020) Biomimicry and Inuit vernacular architecture. Video presentation. Habiter le Nord québécois, U. Laval, Québec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=99vgloTCwdQ

Paquet, A (2022) La transition énergétique nordique vue du Nunavik : Vers une intégration des Inuit et de leurs intérêts dans le processus de production énergétique. Mémoire de maîtrise, Université Laval, Québec. URI : http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11794/71852

Paquet, A, Cloutier, G, Blais, M (2021) Renewable Energy as a Catalyst for Equity? Integrating Inuit Interests with Nunavik Energy Planning, Urban Planning 6 (4). DOI: https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v6i4.4453

Tessier, G (2022) Forme urbaine et transition énergétique au Nunavik : Vers des principes d’aménagement microclimatique pour les communautés Inuit. Essai en design urbain, Université Laval. https://www.bibl.ulaval.ca/doelec/TravauxEtudiants/1346095911.pdf

Tessier, G (2022) Energy and Northern Planning. Video presentation. Habiter le Nord québécois, U. Laval, Québec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLgMtrkDE7E