Paul Parsons

Conference Artic Change (2017)

"We want to be proud of the houses we live in – and that we don’t own. People want to build their own home, to establish their own pride within."

Nunavik’s housing production is managed by three different organizations, each with its own interests and responsibility. Combined with the government’s current social housing regulations and the lack of sufficient funding, human resources, and time, it is very difficult for residents to obtain a house—most importantly, one where they feel at home.

Most families live in standard social housing models which, although easier and faster to build, do not correspond to the Inuit idea of home. Among the most important barriers to the production of culturally appropriate Inuit housing is the notable absence of significant local community involvement regarding planning, design, and construction.

What We've Learned

Realities

Paths for Change

To be culturally meaningful, the architecture of the Inuit home should embody three dimensions of dwelling: symbolic, material, and communal. An Inuit dwelling is a social and cultural place, with meaning invested into practices, aspirations, seasons, local resources, and ingenuity—not to mention deep connections to the land. The true Inuit home is Nuna, shaped into a meaningful, relational, spiritual, and practical space.

Interior and exterior spaces create environments with both symbolic and material qualities, where community life and family cohesion form a world of significant relationships, values, and learning.

Daily cultural and spatial practices are part of Inuit identity. They are both inherited (through nomadic and traditional ways) and influenced by recent frameworks (such as models and policies). These practices define an Inuit dwelling as a grounding “micro Nuna” that is both protective of body, spirit, and identity, and mindful of sharing and nurturing.

Calls to Action

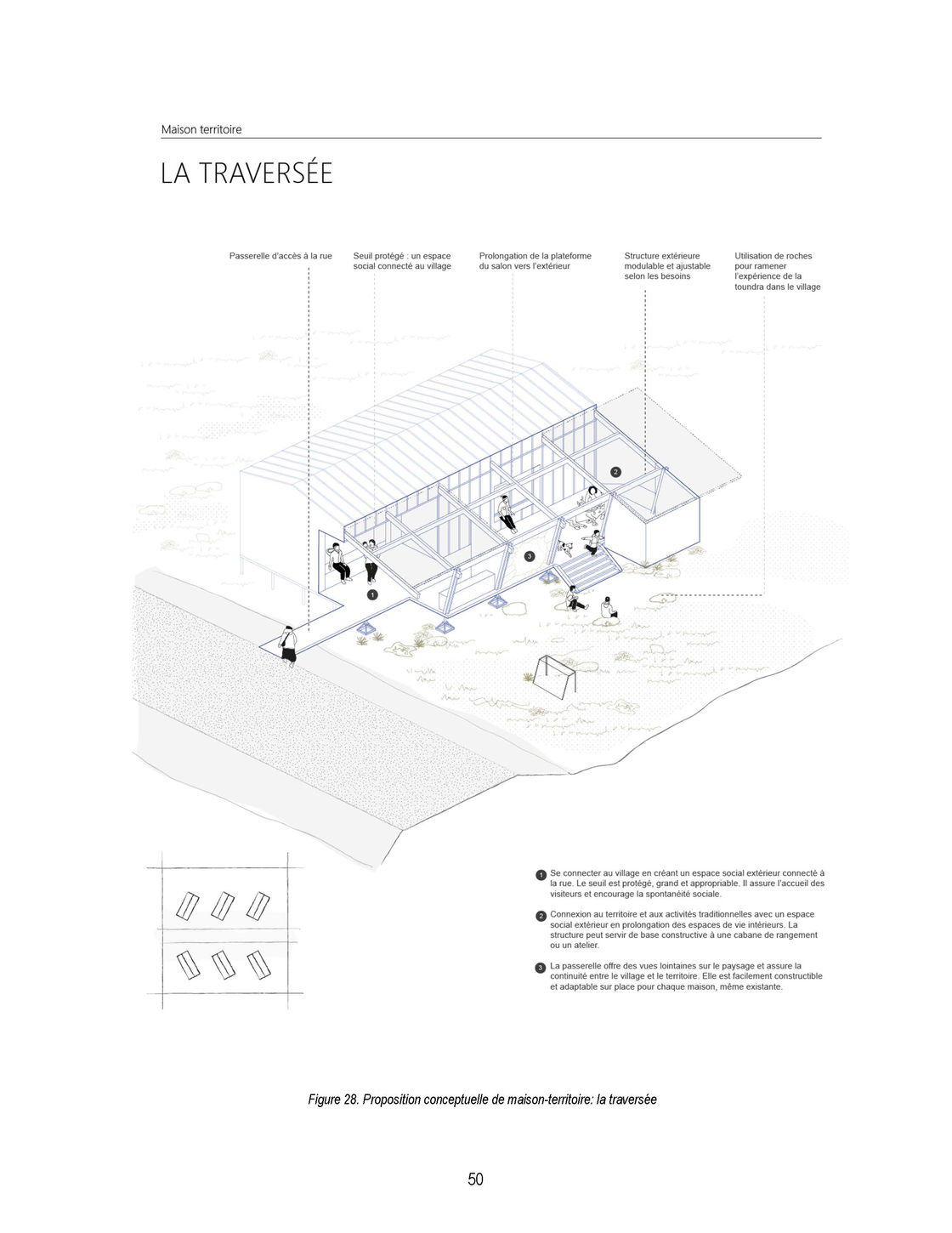

24. Design homes as part of Nuna

Highlight the meaningful connections between housing and the land, by providing views or with thoughtful room orientations or uses.

Ensure a harmonious integration within the natural environment by way of materials choice, a connection to the ground, and adaptation to seasons. (See Wise Siting key)

25. Design homes for family and community life

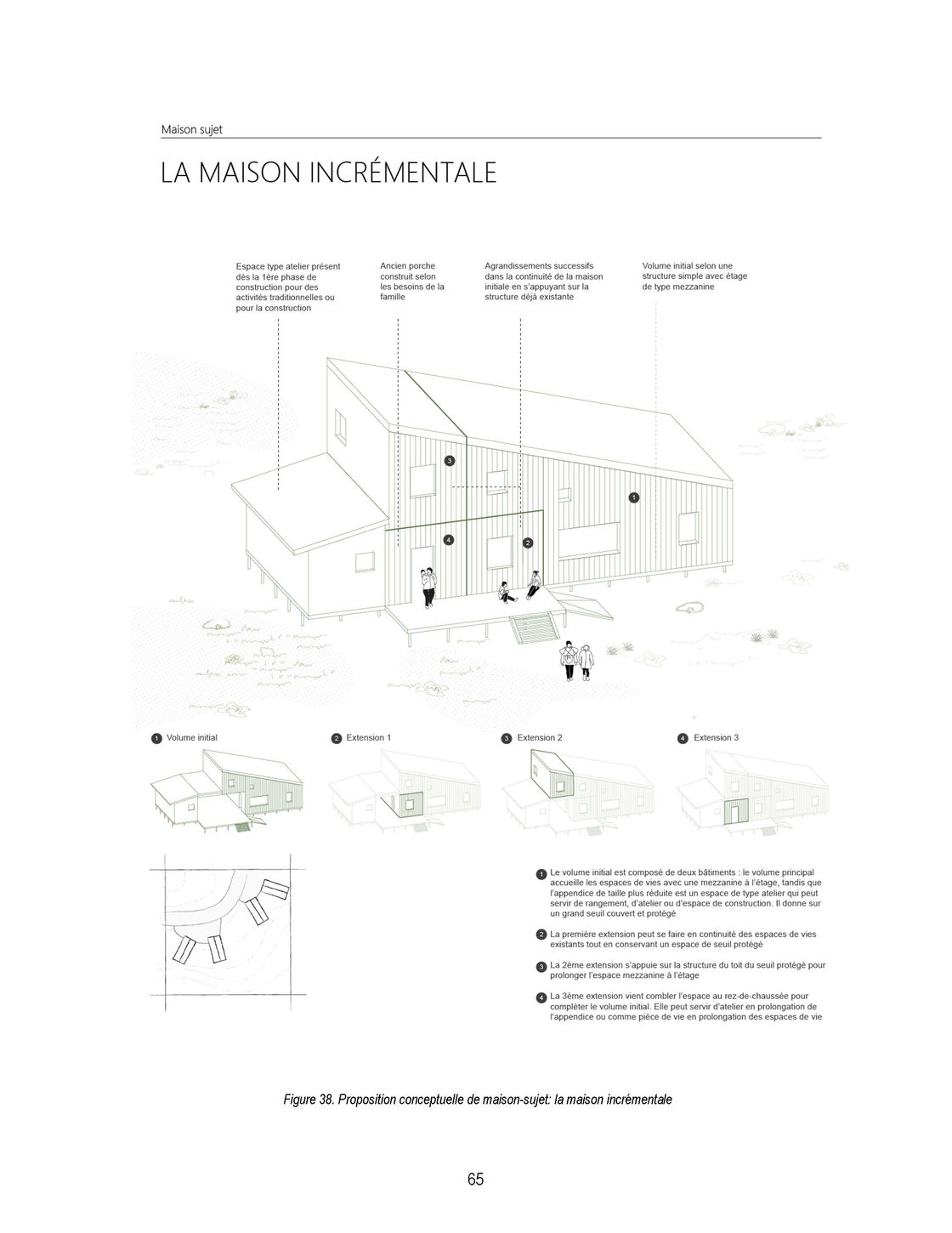

Ensure that housing evolves according to the needs of families and kin by providing choices of types, variety of tenure, and flexible spaces.

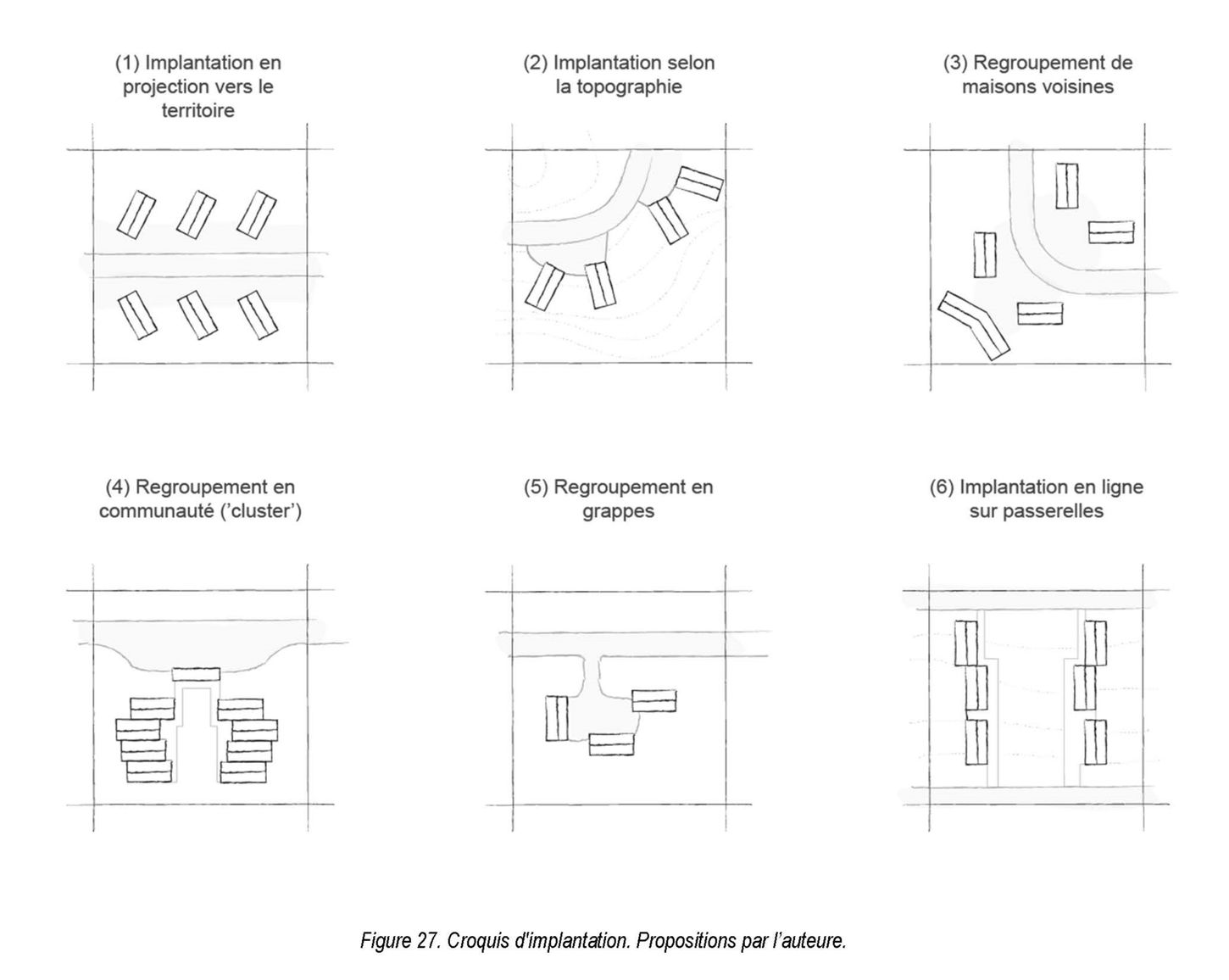

Make dwellings and families the driving forces of vibrant communities by favouring clusters (unifying) over linear configurations.

26. Design homes for today's realities

Provide comfortable and durably built housing that is resilient to the long-term effects of climate change.

Cater to today’s needs through energy-efficient construction, allotted space to work or study, and reliable and affordable Internet service.

27. Include spaces to practice cultural activities

Design spaces adapted for sewing, carving, meat cutting, eating country food on the floor, etc.

Consider the possibilities of practicing these activities outside and adapt the spaces and transitions accordingly.

28. Offer opportunities to personalize

Create spaces to showcase Inuit art and crafts or other belongings by integrating thoughtfully designed furniture and storage.

Think of walls as components of the home’s social space. (See Flexibility key)

Despite a break in the cultural and social link between housing, dwellers, and their way of life, practices inherited from the Inuit nomadic life persist. To strengthen this link, this research examines the Inuit meaning of home and its related architectural qualities.

Housing is considered through three dimensions: home (practices), symbolic (representations), and material (built form). The Inuit home is a micro-universe belonging to Nuna, a space of social and family cohesion, as well as a support for the identity of the cultural and/or family group.

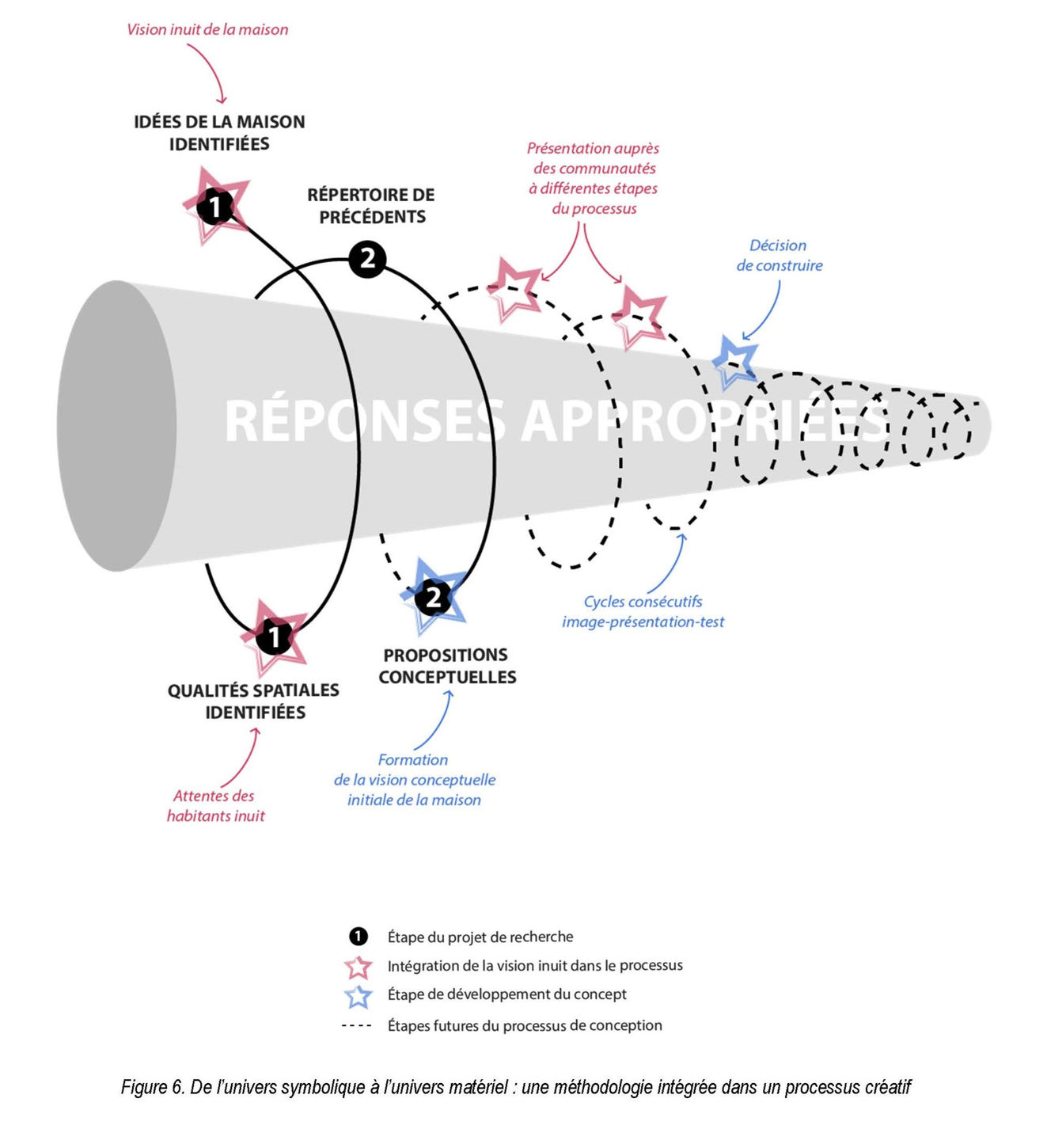

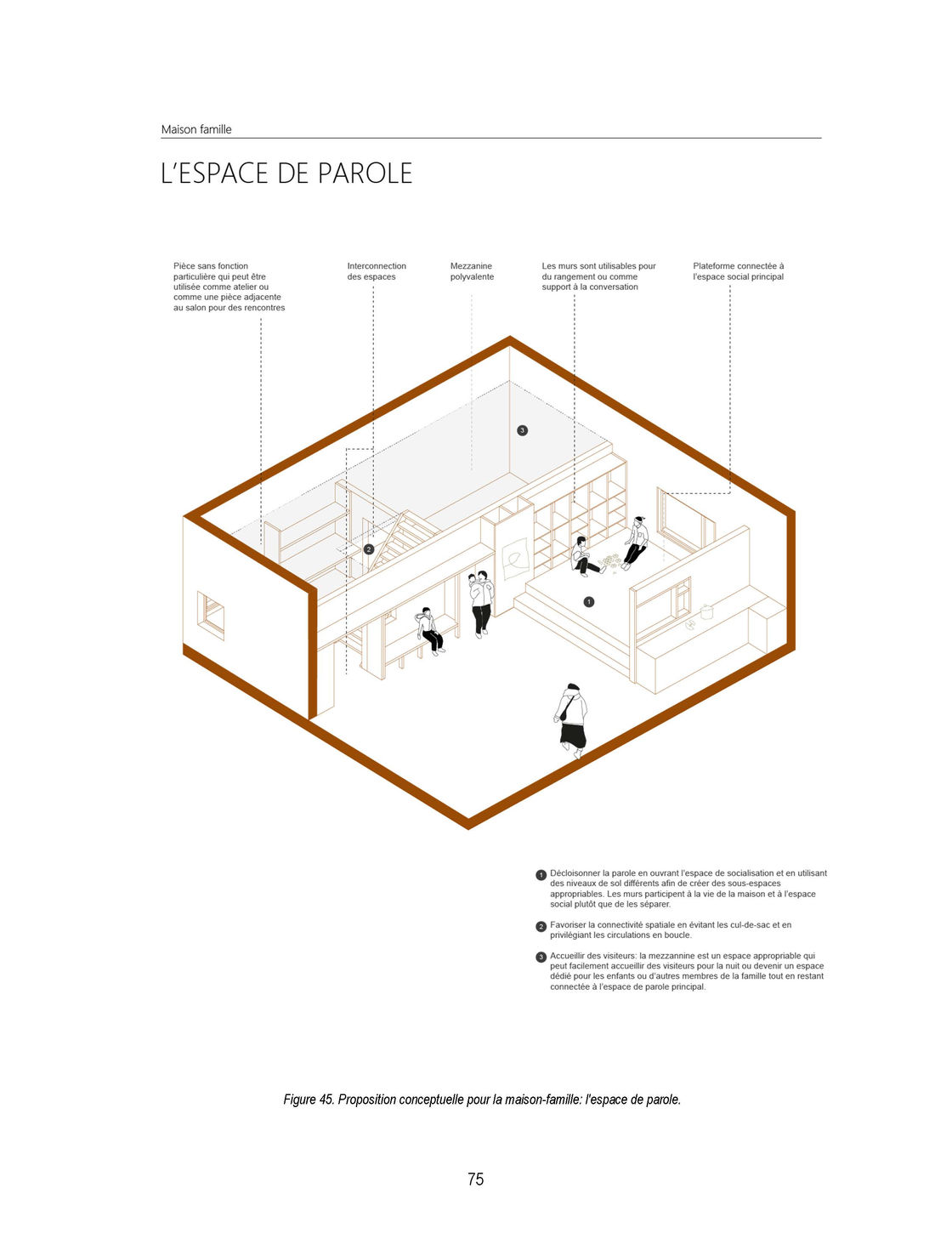

This definition leads to a graphic repertoire of architectural proposals that illustrate the idea of home closer to Inuit expectations. These designs highlight significant qualities for the Inuit home: connecting with the land and community, evolutive and incremental, with inclusive spaces where one can express values, and providing a hearth.

These innovative proposals renew the link between the symbolic and material dimensions of the Inuit home to re-infuse the dwelling and its architecture with Inuit cultural dynamics.

By M. Bayle, research thesis, École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, 2023

Inuit Meaning of Home

Innovations: Thinking Outside the Box

References

Open Acces

Bayle, M (2023) Réflexions pour une architecture significative : univers symbolique et matériel de la maison chez les Inuit du Nunavik. Mémoire de maitrise, Université Laval, Québec. URI : http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11794/113943

Bayle, M. (2020) Réflexions pour une architecture significative : univers symbolique et matériel de la maison chez les Inuit du Nunavik (note de recherche). Études Inuit Studies, 44(1-2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.7202/1081801ar

Blais, M, Vachon, G (2019) Habiter et pensées nomades : Réflexions sur l’architecture des Maisons des jeunes (et intergénérationnelles), Études Inuit Studies 44 (1-2), pp. 237-260. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/etudinuit/2020-v44-n1-2-etudinuit06404/1081804ar.pdf

Brière, A. (2014). L’appropriation de l’espace domestique inuit : enjeux socioculturels à Kangirsujuaq, au Nunavik. Mémoire de recherche, Université Laval, Québec. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11794/25245

Brière, A. et Laugrand, F. (2017). Maisons en communauté et cabanes dans la toundra : appropriation partielle, adaptation et nomadisme chez les Inuits du Nunavik et du Nunavut. Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 47 (1) : 35–48. Archi NA 2543 A58 H116 2017 https://doi.org/10.7202/1042897ar

Collignon, B. (2001). Esprit des lieux et modèles culturels. La mutation des espaces domestiques en arctique inuit // Sense of Place and Cultural Identities: Inuit Domestic Spaces in transition. Annales de Géographie, 110(620), 383-404. https://doi.org/10.3406/geo.2001.1731

Collignon, B. (1999). La construction de l'identité par le territoire. Quelques réflexions à partir du cas des Inuit, d'hier (nomades) et d'aujourd'hui (sédentarisés). In J. Bonnemaison, L. Cambrezy, L. Quinty-Bourgeois (dir.), Le territoire, lien ou frontière? Montréal : L'Harmattan. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers08-09/010014865.pdf Centre Géostat GF 50 T327 1999

Dawson, PC (2006) Seeing Like an Inuit Family: The Relationship Between House Form and Culture in Northern Canada. Études Inuit Studies 30(2) : 113-135. https://doi.org/10.7202/017568ar

Ikey, O (2020) Speaking Out : Introductory, Études Inuit Studies, 44 (1-2), pp. 3-9. https://doi.org/10.7202/1081795ar

Landry, J (2018) Sédentarisation au Nunavik. Identités, territorialités et territoires inuit contemporains. Essai en Design urbain, Université Laval. https://www.bibl.ulaval.ca/doelec/TravauxEtudiants/a2862486.pdf

Landry, J (2018) Nunavik : Identity and territory. Video presentation. Habiter le Nord québécois, U. Laval, Québec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DseE_Wp8jT0

Proulx, S (2020) The inhabiting of Inuit imagination. Spaces in transformation in Inuit art. Video presentation. Habiter le Nord québécois, U. Laval, Québec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WORvOoH6-ts

Other

Collignon, B. (1996). Les Inuits : ce qu'ils savent du territoire. Paris: L'Harmattan. https://www.editions-harmattan.fr/livre-les_inuit_ce_qu_ils_savent_du_territoire_beatrice_collignon-9782738448491-14451.html

Dawson, P.C. (2008). Unfriendly architecture: Using observations of Inuit spatial behavior to design culturally sustaining houses in Arctic Canada. Housing Studies, 23(1), 111-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030701731258